|

Motorcyclist Illustrated September, 1975

|

part 0

by Fergus Reilly

Ossa 250 Enduro Review

4216 klms

Kelty, Scotland

July 7th, 1974

(day -58 - 0 klms)

to

Kelty, Scotland

September 2nd, 1974

(day -1 - 4216 klms)

|

|

THE Ossa 250 Enduro is definitely built to take a hammering

off the road. Extremely low gearing and knobbly tyres make

traveling on tarmac tedious to downright uncomfortable

and positively nerve-racking in the wet; the lack of rubber in

contact with the road necessitates low speeds, causing each

kn0b’s impact with the road to be felt distinctly. In addition

the narrow seat becomes a blunt wedge, and after about six

hours the impression is of slow bisection to all but the maximally padded torso! |

it must be capable of getting me across Africa

|

|

The bike carries the minimum street-legal equipment, but on the bike tested the horn ceased functioning after two

hundred miles, and the tin-plate and chewing-gum switch-

gear required much filing and waterproofing to ensure its

working, without having to stop and take a hammer to the

plastic toggles.

Speaking of electrics, the bike tested carried a rusting

ignition switch, ingeniously positioned to permit insertion of

the key only when dismounted and, if fitted with a key ring it

is switched off by the weight of the ring over bumps - highly

alarming and dangerous on country roads, let alone embarrassing on the rough. The high beam indicator was absent,

the kill button disconnected and the fuse drained about four

of the available six volts from the battery. Apart from that

the battery is virtually inaccessible, being surrounded by

large fibreglass sections, which admittedly look good and are

easily fabricated, but are detached with the greatest difficulty - requiring more tools than are supplied with the

bike. On the credit side, the 5in Italian sealed beam lamp is

excellent when the switches can be coaxed to transmit current to the filaments; there are pressure contacts for the

stoplight on both front and rear cables, but these did require

dismantling and trimming with rubber to allow effective

contact of the metal bits.

The bodywork is entirely of fibreglass and looks great, in

red and white on the tested '74 model better than most road

bikes. But, maintenance and removal is difficult since they

have tried to get away with too few pieces and the nut and

bolt fixtures require groping about before the battery is revealed.

The underseat compartment is of a suitable shape

for storing plasticine, but tools require careful juggling

before the seat can be replaced. The sections are unfortunately designed such that water runs into the underseat space

and thence to the battery compartment, both of which have

drainage holes drilled on the right, whilst the bike leans to

the left on its stand, leaving tools and battery sitting in up to

½in of water - the supplied tools were rusty within two days

of delivery in a reasonable dry Scottish May.

So the trimmings, most of which have been forced additions due to regulations, are not up to much, but then this

machine, in its intended use, is not meant to rely on them.

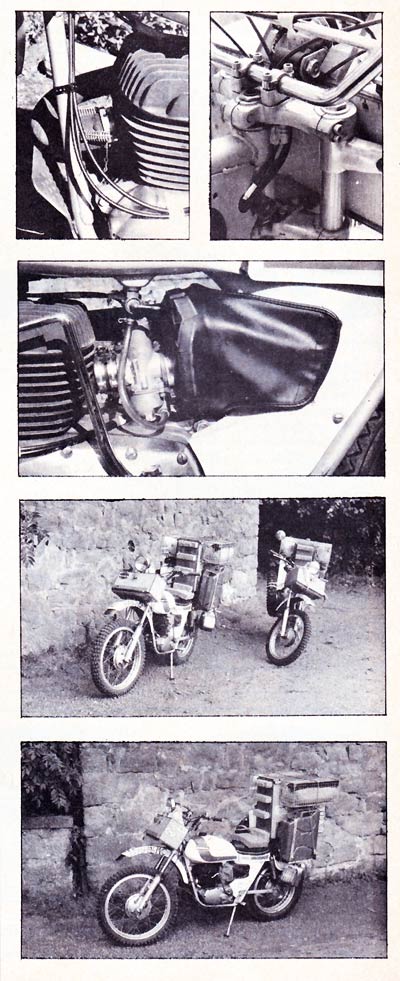

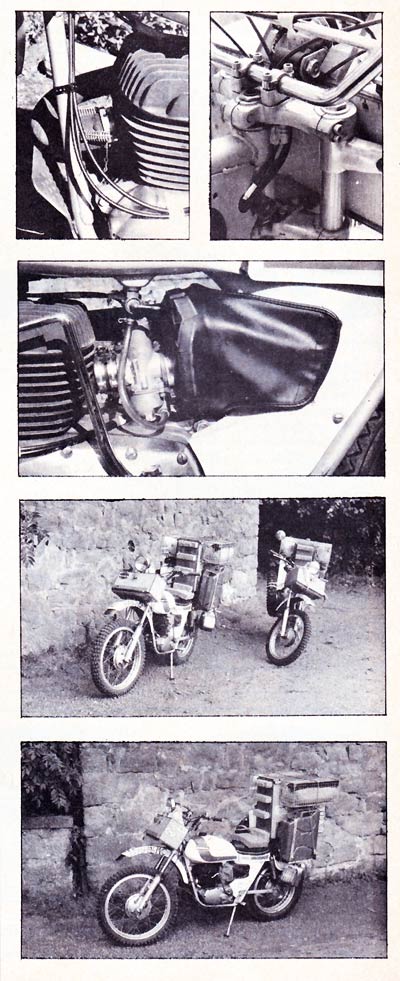

The motor is a very good unit, providing a wide powerband

which does not lack for horses anywhere. In fact it proved

almost impossible to stall the bike in first gear. The exhaust

gases pass along a business-like silencer, which is rather ugly

and ill-positioned; the chrome anti-burn frame permits

thigh-manifold contact in odd unguarded moments which

can be nasty! Fire is supplied via magneto and electric

pointless ignition in the form of a neat, compact unit beneath

the tank and leaves space for a pint of oil (provided you can

devise a simple method of attaching it which allows access

without a major strip).

Getting the bike going is not easy. When cold. the 32mm

Amal requires excess flooding, achieved by tucking the

overflow pipe up behind the exhaust whilst tickling. Then

the left side kick starter necessitates, dismounting before it

can be seriously attacked, a major balancing feat is required

if the bike is not on level ground, hanging over the bike

blanket-wise to reach the throttle whilst kicking the long

starter and avoiding an undignified sprawl on the ground.

To cap it off, the leg must be smartly removed left to avoid a

painful smack behind the knee as the starter snaps back and

snaps neatly away with a loud clang. In fact, on a cold morning, one can become crippled before getting the motor moving. |

Then there is the problem of stalling in heavy traffic -

well it is a good way of losing weight.

The single, 243.8cc two stroke piston-ported pot, once going. is a delight to hear and control. The Amal carb is simple

and easily adjusted to provide an adequate supply of go-

juice, although the pilot jet fitted appears to be suited mainly

for competition use as it has a tendency to produce clouds of

smoke or alternatively pre-ignition - after a work-out with

the adjusting screw hanging perilously far out. Nevertheless, when the appropriate mixture settings are selected the

motor is powerful, responsive and relatively quiet.

Although the gearbox contains a nifty direct drive in top

(fifth) it is difficult to work with grace! The 1:1 top ratio has,

I suspect, cost a few tight squeezes in the lower four which is

revealed in an almost task finding first when the engine is

hot. Neutral is no bother as there is one between each pair of

gears. Changing is not helped by a gear lever which lies 2

inches forward of a size ten boot, so that it is usually activated

at the hip; tiring on a long session when one finds oneself

repeatedly kicking hard, especially up to fifth and down to

second, with the sticky false neutrals between all gears. Moreover the lever is so positioned to take a clobbering on a left

hand fall pushing it into contact with the inspection plate.

This can be rectified easily with a shifting wrench and

preferably a vice! One wonders why a bike so obviously de-

signed for being dropped and thrown about should have such

a fantastic, solid ¼ in Dural crash plate and such a vulnerable

shift lever. Both gear lever and brake pedal are wired to the

frame.

Initially, I found the suspension springing inadequate, but

experimentation showed that the fourth setting of the five

available on the rear supports will carry 12 stones over most

terrain without bottoming. The front fork gave near perfect

performance after it was stiffened with 20/50 oil.

The double-loop, cradle frame is solid and in fact, purpose-built for ISDT type treatment. Although cut rather

short at the rear, it has excellent weight/strength characteristics. The wheels are similarly strong and light, but the

aluminium spoke nipples are short term and are likely to

seize and break the spokes after a while, far better to

sacrifice the two ounces and replace them with brass nipples

which would provide a lifetime commensurate with the rest

of the machine (bar the electrics).

Top speed is specified as 85mph, but vibration increases

after 50 mph, and with knobbly tyres it is difficult to imagine

conditions which would facilitate 80 plus in relative safety.

Once going, stopping is not really so easy as the 6.2in drum

front and rear are adequate for a controlled coming to rest

but inadequate for emergency stopping. The cables are all

protected at both ends by very neat lever dust covers and

mini-gaiters which is so sensible, neat and attractive that you

wonder why they aren’t standard equipment on most bikes.

Although the bike is clearly modeled on factory ISDT

entries its handling and low-speed capabilities would place it

in good stead for the Scottish, it is very happy to pick its way

up rocky gullies, climb boulders, plough through mud and

generally take a sedate stroll over the “hielandsâ€. Even a

cursory glance at the rubber mounted carburetor and mud,

dust and water-tight cover over the filter confirms that the

Ossa is built for rough country and rough treatment.

To sum up, the electrics are shocking, but the bike is

strong, simple, looks and feels reliable, handles superbly in |

|

the whole spectrum of off-road conditions and is good value

fuel-wise (up to 120 mpg on the road). It needs little

modification for serious competition; in fact it is oriented to

such with little serious concession to the non-competitive

rider and at £529 (May 1974) you should think carefully — it

is not a trail bike, it is an Enduro. But what the hell, I am

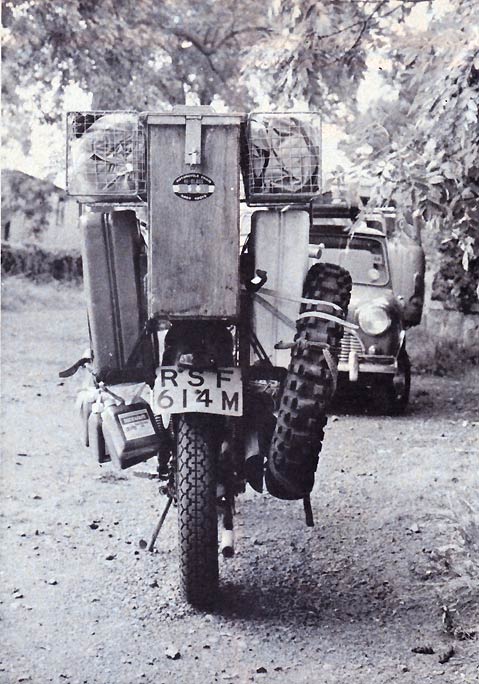

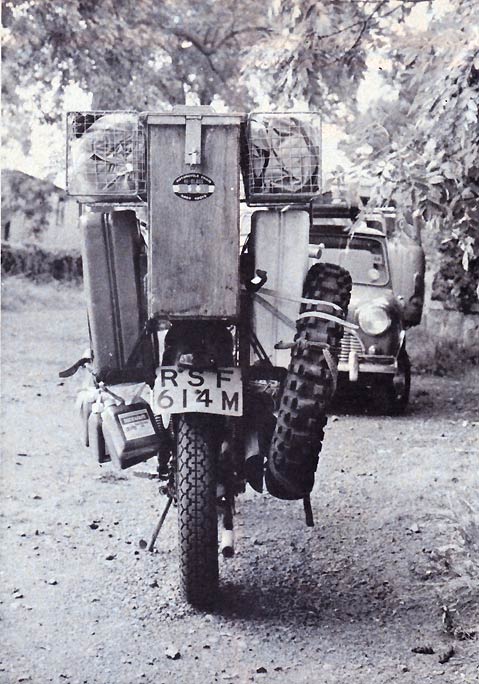

taking my Ossa 250 to Africa! You can read all about the trip

in future issues of MCI. |

SPECIFICATION 250 E 73

- Engine two stroke single

- Bore and stroke 72 x 60 mm

- Displacement 250 c.c.

- Compression ratio 1 1 ,5:1

- Carburation 32 mm AMAL Rubber mounted

- BHP @ RPM 28 at 6,800 RPM (rear wheel

- Lubrication oil mist 5 %

- Gearbox 5 speed

- Gear ratios 5th 1:1, 4th 1:1.35, 3rd 1:1.82, 2nd 1:2.45, 1st 1:3.60

- Clutch multidisc wet

- Ignition motoplat electronic

- Brakes light alloy 163 mm diameter x 41 mm wide; water and dust protected

- Wheels and tires 4.50in x 18in, rear 3.00in x 21 in front

- Fuel capacity 13 litres 2.8 gals

- Weight 96 kg 212lbs

- Wheel Base 1.360 mm 53in

- Ground clearance 230 mm 8.75in

|

|

|

|