|

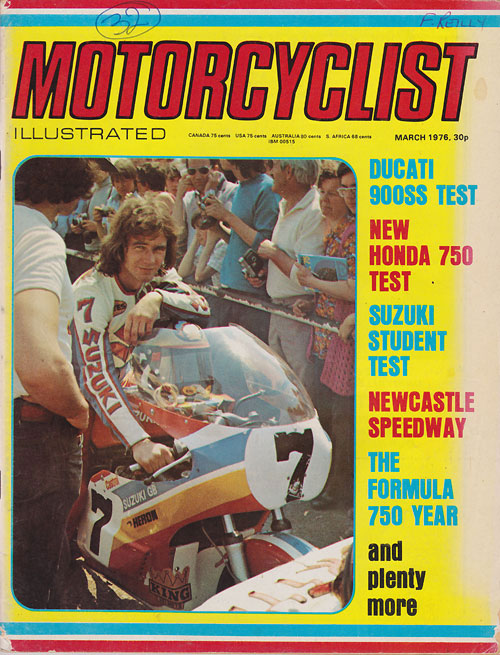

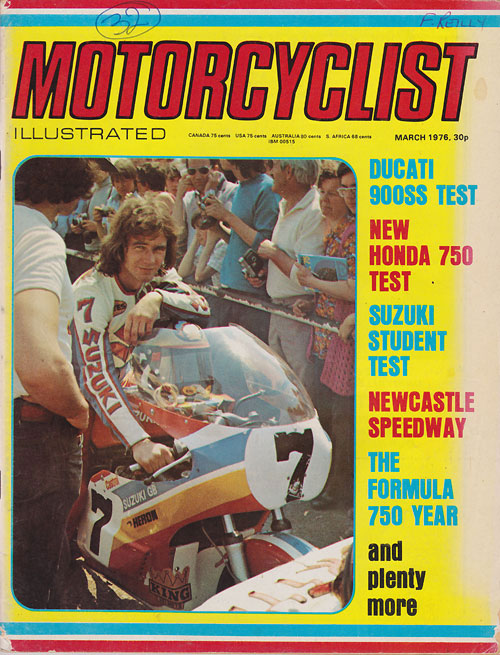

Motorcyclist Illustrated March, 1976

|

part 6

by Fergus & Sharyn Reilly

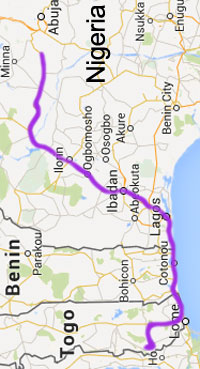

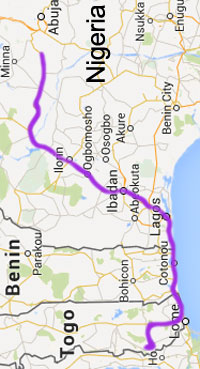

Gulf of Guineau

1673 klms

Gurara Falls, Nigeria

January 5th, 1975

(day 124 - 17585 klms)

to

Kloto, Togo

January 24th, 1975

(day 143 - 19258 klms)

|

|

The jungle began a few hundred

kilometres north of Lagos. thick, green, steamy and with fruit in

abundance. The fruit stalls in the villages became more and more

prolific. Unable to resist any longer we decided to stop in a small

village. instantaneously we were surrounded by the entire female

population each one determined to sell us fruit. Ten minutes later, our

bikes were sprouting fruit all over, our pockets were full and I was

suffering a wound from a pineapple brandished by an eager saleslady.

As we traveled closer to

the capital, petrol became increasingly more difficult to get. The

transport drivers were on strike. But, in Nigerian fashion they did it

with finesse. Each driver deflated the front, outer tyre on his truck,

laid a warning trail of stones and branches behind his vehicle and lay

down in the shade. We must have passed two hundred similarly afflicted

vehicles.

We were desperately in need of petrol. After stopping to

ask in a village for black market petrol which we had so far not

managed to find, a car stopped beside us, the guy jumped out, flashed a

smile and offered us petrol free from his tank! |

|

|

|

|

We reached a town where

everyone assured us that there was one service station open. There were

literally hundreds of people carrying containers of every description

queuing for petrol and kept in line by several burly gun-carrying

policemen. Every now and then they decided the people were getting

over-anxious and pushed them back, one by throwing his shoes, then there

would be crashing and shouting as people and cans went over.

Fergus went off in search of a container, when another

surge erupted. He reappeared with a bleeding man, dazedly rocking at

his side. After yelling for water, bandages and a breathing space,

Fergus turned to the guy. He happened to be the service station manager

who miraculously parted the crowd with help from the police for our

bikes to come forward and be filled. |

The jungle seemed less fantastic very rapidly when we decided to stop

for the night. It was difficult to find an opening in which to ride the

bike, let alone pitch a tent. We had an abortive attempt when Fergus

wedged his bike in a ditch and had to be helped out by two of the

striking truck drivers. Then we decided to opt for a cocoa plantation.

It was beautiful; totally covered in foliage and inside of foot deep in

fallen leaves. In this climate the temperature doesn't drop in the

evening, so although we lay back on a bed of comfort, we sweated and

beat off the mosquitoes all night.

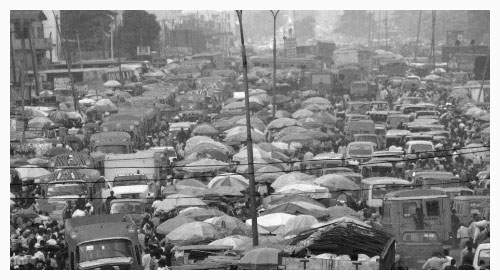

Within five minutes of

sighting the outskirts of Lagos we were caught up in a bumper to bumper

traffic jam. Dutifully we kept our place, spluttering on the fumes of

exhausts spiced with heavy tropical atmosphere. Then we reached a

policeman on traffic duty. He nonchalantly directed us to the path along

the side of the road as if he thought we were fools not to use the

obvious.

So, we rode the rough into the heart of Lagos. Whilst

the buses, taxis, cars, trucks and motorbikes hooted their horns and

brushed with death in the most hair- raising driving I've ever

witnessed, we only had to dodge pedestrians, animals and enormous holes

in the path. |

|

|

Totally confused by a city faster by far than London, we stopped at the

GPO. Again an instantaneous crowd of hundreds surrounded us. This time

firing questions and not believing us that we had crossed the desert.

What had we eaten and how would we have coped with the savage animals

and impassable rivers. William, a big burly sailor, took pity on our

obviously bewildered state and offered to lead us on his Honda to the

address of an old friend we'd known in Scotland.

|

|

We arrived at an ex-colonial

mansion now inhabited by the warmest, blackest family I know. We spent

the rest of the week being spoilt rotten by our friend's family. Usually

the family and two servants would sit on the back verandah and when

visitors came, the five minute traditional Yoruba greeting ensued. The

newcomer would kneel on the ground all this time. Bode, our friend

laughed at our amazement; the correct posture for the ritual is to lie

prostrate on the ground!

In Lagos, the Yoruba people predominate and they are

loud, noisy and fun-loving. Bode's girlfriend was introduced to us as

the "Princess of Lagos". Her father is the traditional King. Although he

is a graduated pharmacist from a British university his lifestyle is

relatively unchanged from his ancestors. He has several wives and loads

of children who live in the Palace, the original wooden and mud brick now

extended by a modern concrete and glass building. His subjects rarely

see him, so that the mystery and awe surrounding his status are

preserved. |

We spent a day at the Palace, to watch a ritual thanking of the King by a

group of people who came to settle in Lagos hundreds of years ago.

While the King's family watched, dressed in impeccable London fashion,

the newcomers, a sect who claim to feel no pain, carried in vast

towering masks and brought welts out on their skin by thrashing

themselves with twigs. The King did not appear, and after his personal

bodyguard signaled he would not come out on this occasion, the drumming

group left.

Lagos is a city of extremes.

The ex-colonial area, now the homes of government officials and

embassies in plush and discreet. Huge mansions are set in clipped

gardens. and chauffeur driven cars sweep up the driveways. While the

area surrounding the King's palace, the real Lagos, is noisy, crowded

and jumping with life. People spend most of their lives on the street;

they eat, sleep, wash and on special occasions they block off the

street, hire some trestle tables and everybody from babies to grandmas

dance and drink the night away.

In Northern Nigeria we had heard the Zaire border was

also being closed. Northbound travellers told tales of anti-white

propaganda and being stoned in some areas. Whilst we were in Lagos the

border closure was confirmed. After thinking it over it seemed the best

solution was to give up our plan to ride to the Cape. Instead, we would

go West, take our time wandering where we chose and then work out how to

get to Australia. |

|

|

We said goodbye to Bode and his family and promised to come back. Two hours later we still had not reached the Dahomeian (now called Benin -ed)

border which was only 40 kilometres away. We were lost! We turned back

and an hour or so later found the un-signposted turning to the border.

We were to find that ex-French territories were always well signposted,

whilst in ex-British countries you were lucky to ever find one.

|

|

Once through the border the

scenery changed almost instantly. The jungle became less dense and

people less clothed. Nigerians were the most sophisticated of all the

people we met. Towards evening we pulled off into some sparse bush near a

small village. Immediately half the village came over to see what was

happening. We dutifully asked the Chief's permission to camp. He was

delighted and camp was set up in the quickest time ever, as various

helping hands jumped to our aid.

Most of the people wandered back to the village later in

the evening, but of the few that remained there was one man whom I

found very disconcerting. He spoke only to Fergus, but with an uncanny

clairvoyance named the place we had stayed in Lagos and said some names

which later I found out were scientists Fergus admired. He then wrote

some un-intelligible words on a piece of paper and asked Fergus to write

down his name. Then just as strangely he wandered off, but not to the

village. |

Dahomey is the centre of juju (black

magic or any other names to describe the supernatural events that do

happen in Africa). I really believe the man possessed some strange

powers. The next day we went to cash travellers cheques and were given a

rate three times more than we should have by the bank teller.

Immediately after, we were just leaving the town when a young guy

overtook us and signalled us to stop, and then offered us accommodation

for the night. He and his wife were really enjoyable people, who

happened to live next door to a guy we had met in the desert.

As we discussed the desert we mentioned our friend Jacques the

priest. The young guy looked astounded, Jacques had been a great friend

of his and he'd lost contact with him for five years. Juju? We wondered

then, and do now.

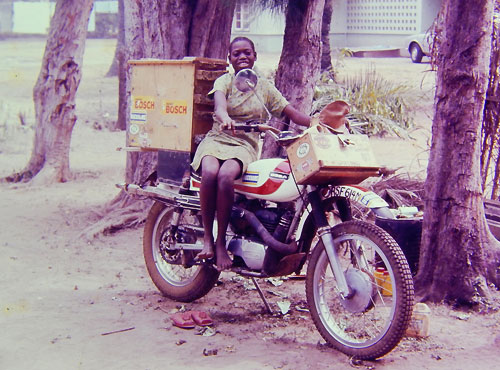

We followed the coastal road

towards Togo. We stopped to rest near a village dispersed on islands

and along the banks of a wide estuary. Two young boys appeared and

invited us to their village. Village hospitality is amazing. We were

offered Cokes, now sold even in the remotest parts of Africa and kept

cool in buckets of water. Then they took us for a ride in a dugout

canoe.

The fisherman were standing in shallows casting huge

circular nets which they let rest a few minutes and then pulled in and

loaded their dugouts tied to a stake. Whilst women set small cane traps

for crabs. Our friends took it in turn to use a long pole to glide the

canoe through the water. We watched a boy. perhaps 4 years old imitate

his father's action with a small pole.

The evening was indescribably peaceful as canoes glided

noiselessly over the water, carrying returning fishermen, water

gatherers and school children to their homes. Our campsite for the night

was equally idyllic. We pitched the tent under a coconut palm on the

beach. and watched the waves crashing in until nightfall. |

|

|

We crossed into Togo and its capital Lome. The tropical beaches

obviously attract a wealthy tourist population. Huge modern hotels and

nightclubs lined the beach front, in our filthy bike clothes we didn't

dare go to one of the pubs, so headed northwards. The jungle rapidly

became sparser, and the sun hotter. After inquiring at the police

station we discovered Jacques lived in the seminary perched high on a

hill overlooking the town. Not before a hair-raising hill climb over

large rubble did we make it to the top. Jacques and his fellow priests

welcomed us and offered us beds for the night. We accepted gratefully.

|

|

We moved further north and

the sun got hotter, so hot that we hardly ventured out of the shade at

midday. We decided to rest up in the forest where we hoped we would find

cooler conditions in the mountains between Togo and Ghana.

As we neared the mountains the road rose and fell

steeply through tall rain forest. We found a tiny track leading off into

the bush at the top of a mountain, and decided to try to find a

campsite. As we sat by the roadside soaking in the smell of damp fresh

air, a young boy appeared. Did he know where there was water and a place

for a tent? With a delighted smile he led us across the road and into

what we later discovered was a local farmer's cocoa plantation. Just a

few yards in was a clear, fast-running stream, a bed of soft leaves on

which to pitch the tent and just enough room to squeeze in the bikes. |

The rest of the day was

spent talking to a never-ending visitation of small groups of people,

who came into see our encampment. We were not far from a village and the

word had passed that we had arrived. The old farmer on whose land we

were arrived with a bucket of wild grapefruit. and his three small sons

in tow. These three became firm friends of ours; each morning as we

awakened to the sound of the women collecting water, they would

Invariably be waiting patiently outside the tent for us to emerge.

The farmer's number one wife invited us up to their

house. We walked up through a coffee plantation which opened out onto a

clearing on top of the hill. African hospitality demanded that we have

the only two stools. We spent the afternoon watching the chickens. ducks

and guinea fowl scratching below the coffee bushes, while we ate boiled

yams and drank palm wine. The wine is tapped every few days from a

certain type of palm and drunk fresh. It certainly cast a peaceful lull

over us as we sat dozily in the shade.

One day the three boys excitedly asked us to see a

magician who was coming to the village with them that night. Back they

came draped in their best cloaks of bright material and their eyes wide.

By now we were equally excited. We stumbled along in the dark, but when

we arrived at the village we were told the chief had refused

permission. In Togo, by law, a magician must have a certificate from the

president stating that he can be decapitated without harm.

The magician did not have this paper and it seemed the

chief did not want the responsibility of a potential death on his hands

Every day we put off leaving. it seemed so hard to leave the people, the

weather and the campsite. |

|

|

|

|

We were curious how all the village children seemed

to disappear after school - it transpired that they went to help fill

the water cisterns at a nearby building called Chateau Vial which, we

were told, was well worth the visit. Getting directions we set off for

the short journey to this “grande maison”.

It turned out to be a steep 2Klm climb up a winding track in poor repair

but when we reached the top we were well-rewarded with the vision of a

classical French-style chateau in full detail sitting atop a mountain

in the Togolese jungle.

|

We spent some time roaming round this extraordinary complex which we later discovered was the presidential castle (see Chateau Vial on Youtube), a paradise in the Kloto.

For the record, it housed the cabinet of ministers under General

Gnassingbe Eyadema regime. The presidents Abdou Diouf of Senegal and

Felix Houphouet Boigny of the Ivory Coast, the first Togolese Minister

Joseph Kokou Koffigoh and Edem Kodjo also stayed.

At last we found the village children - they were carrying buckets of

water on their heads from the stream at the foot of the track up a steep

and rocky foot track to the internal water cisterns in the Chateau. We

were stunned - the kids, some as young as 5 years old, see,ed very

nonchalant about carrying out a task which I doubted I could do - even

on a good day. I must admit we wondered what the kids were paid for that

extremely arduous toil.

Returning to our camp we reluctantly admitted our visas were near

expired. so we set off for the nearest crossing point into Ghana.

|

|

|

|