|

Motorcyclist Illustrated April, 1976

|

part 7

by Fergus & Sharyn Reilly

Togo and Ghana

1893 klms

Kloto, Togo

January 25th, 1975

(day 144 - 19258 klms)

to

Sansanné-Mango, Togo

February 22nd, 1975

(day 172 - 21151 klms)

|

|

We maneuvered a jungle track which followed a gorge cut by a rushing

stream for several miles of “no-man's land” between Togo and Ghana; an

area reputed to be filled with desperate bandits by those safely within

the borders of the two countries. We did not see any likely desperadoes

just a man and his family who seemed to look at us in return as possible

head-bashers and thieves.

In a clearing in the jungle was the border post. We were obviously a

rare occurrence. The guy in charge welcomed us, sat us down and even

offered us cigarettes. After about a half-hour of conversation he

apologisingly asked us to fill in an entry form and perhaps could we

show our passports? Another half-hour later, after everyone discussed

the relative merits of the two alternative routes to the nearest town

fifty or so kilometres away, we left bathed in euphoria at the

comparative ease of entry.

|

|

|

|

|

As we ploughed through up to two feet of fine red dust our happiness

wore thin and we finally reached town covered in red and gasping for a

drink to wash our parched throats. But first we needed money.

We went to the bank and asked to change a traveler's cheque. The

manager looked up the rate of exchange in the daily paper and went off

in search of forms. Meanwhile the two tellers were grimacing and making

signs at Fergus to come over. One of them offered a rate better than the

paper. The other then bettered his colleague. For the next half hour

whilst the manager mysteriously never appeared the two of them carried

the rate higher and higher.

Just in time the manager returned with money for us, and despite their

lucrative offers we left in search of a cold drink and the knowledge

that we would not change any more money in a bank in Ghana.

We headed towards Akosombo Dam, a symbol of the height of Ghana's

previous wealth when Nkrumah was still popular. It was impressive, but

the town which had been built beside it had not really developed as

planned. The modern, European style town on the hill is fringed with a

shanty town jumping with life.

|

It was now getting dark so we started looking for a place to camp for

the night. But there was absolutely nowhere. Every available piece of

land was cultivated with sugar cane or else was in a heavily populated

area. In desperation we pulled into a side road marked by a sign reading

“Caledonia Hotel”. The first and only time we stayed in an hotel proved

to be of mixed delights. The bed was comfortable, but clouds of

mosquitoes flew in through the windows which had to be open to prevent

suffocation.

We spent some time drinking in the bar and trying to decide which way

to head next. Our map which had never been proved wrong so far, had a

game reserve marked close by. This amazed everybody in the bar as

several had relations living in the area and nobody knew of any game

there. It seemed our map was wrong.

The rest of our time in Ghana proved that the map was often wrong, but

only in Ghana. Coupled with the fact that road Signs do not exist,

Fergus navigated by the sun the following day when we headed towards

Boti Waterfall, which we desperately hoped would be real and not just

another mythical place on our map.

|

|

|

|

|

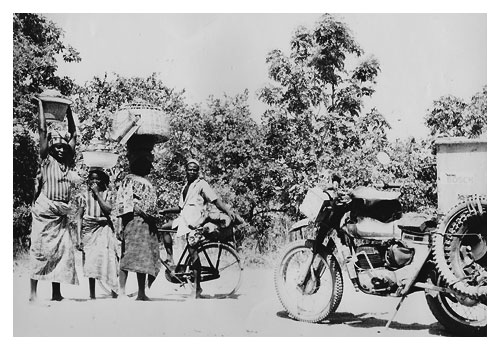

On the way down a heavily corrugated track we met a woman with her

three daughters strung about with every conceivable colour of bead. Not

only did she know of the waterfall, but she also offered to show us

herself. We left the bikes by an impressive bungalow, the rest house,

and descended into the bowels of the earth down over five hundred steps.

At the bottom was a huge amphitheatre. down which the waterfall crashed

into linking pools. Unfortunately only a trickle ran over the rocks; it

was the dry season. Still, the woman explained it so well we thought we

had seen it anyway.

The caretaker of the rest house arrived back and offered us a room at

an exorbitant price as we had not booked at the government office. In

true African style when we refused and said we would pitch the tent he

laughed, offered us all the facilities and invited us up to his house to

play cards. Fergus might be a mathematician. but not even he could

fathom the rules of the game. Instead we sat and watched games pass at a

furious pace with much shouting and slapping down of cards.

|

Now fully conversant with the system of booking into the Government

Rest Houses we set off for the nearest office. only to find that the

rest house we wished to stay at 20 kilometres from Accra was booked at

the premises. By now we knew not to be upset by a mix up like this;

Ghana's bureaucracy grinds slowly, and we hoped, surely.

At the rest house set in a huge Aburi Botanical Gardens we were made

welcome and shown to our room. For less than fifty pence we had a vast

room and bathroom with the use of an even larger sitting room which had

a fridge. Ecstasy was ice cold drinks. Three days later we managed to

drag ourselves away from the luxury of Aburi rest house, formerly the

holiday spot for early colonial administrative officers.

We decided to opt for luxury again in Accra and try to stay in a

rest house. Sadly the officials in the office told us that some were half

built, others not yet started. but one of the messengers could show us

other departments to try. Several hours later we returned hot and tired

and with the knowledge that the housing shortage in Accra had turned

rest houses into permanent dwellings. The messenger, Jonathon, offered us

a room at his place for the night.

|

|

|

|

|

Jonathon began to worry us slightly when we arrived at his home and he

went to enormous lengths to protect our belongings from the vicious

thieves he claimed that prowled the neighbourhood.

When he insisted that we take the two bikes inside his tiny two-roomed

house with us, we knew that although he was generous he was rather

peculiar as it was impossible to enter the house if the bikes were

inside we managed to persuade him that we would be happy to pitch our

tent in the yard and sleep near the bikes.

We spent the next few days exploring Accra, a big but attractive city.

People were very friendly. Often the bikes attracted attention and we

would be asked where we had traveled; inevitably on hearing, the

questioner would grin, pat us on the back and exclaim “you have really

tried!”.

The government had a strong campaign for everyone to grow their own food

and it seemed to be working. Most available space in Accra was turned

into a vegetable patch, although we found the radio propaganda

disturbing it was obviously successful.

|

Nights in Accra became increasingly difficult. The heat and mosquitoes

were unbearable and Jonathon's behaviour was becoming stranger. He told

us he was married to a woman living in the sluggish stream behind his

house and that his son too lived below the water.

Each night his stories of juju killings became wilder and more

incoherent. We didn't know if we were putting a strain on him by staying

and though all the neighbours were incredibly kind and often gave us

fruit, even they looked askance at Jonathon.

It got us down and we left. to scurry back to the peace of Aburi gardens.

We went to visit friends in Aburi that we had met before. the Kente

weaver who made cloth by weaving strips four inches wide on a primitive

loom in complicated geometric patterns and the chief security officer at

the gardens, who had introduced himself to us as the man in charge.

It was good to spend time with these relaxed people after our tense time in Accra.

One day in another small town nearby a young man came up to us and

started talking. He invited us back to meet his grandfather. The house

was an English bungalow called “Patience Lodge”, and the old man told us

he had brought the plan back from England when he had been at

Cambridge.

He was a very unusual man. His family were wealthy cocoa plantation

owners, who unlike the majority of Ghanaians had prospered under the

British. He had achieved a high post in the colonial administration and

had traveled in that position. He was a very “pukka” old black

gentleman, a type of person I had not known existed.

We spent a beautiful afternoon looking at old photographs of his wedding

with all the men in top hats and tails, and all the women in long

frilly dresses, of himself playing tennis and cricket and in groups of

colonial officers where often he was the only black. He was the only

African we met who missed colonial rule.

|

|

|

|

|

Our visas were running short so we headed back towards Togo along the

coast. As we rode towards the border we saw more and more signs

advertising fetish priests, licensed circumcisers. male and female, and

innumerable crude wooden figures often smeared with blood. Fishermen are

traditionally strong believers in Juju and almost every village had a

shrine warding off evil spirits.

When we left the main road and followed a narrow road linking long

narrow islands of land, the signs were even more prolific, but we didn't

feel too worried as almost everyone we passed beamed a smile and waved.

We found another peaceful rest house. in a remote town, about half-a-mile

from the sea. It was burning hot so we set off on foot towards the palms

marking the shore. First we gingerly negotiated our way between the

rows of a cassava plot, then across scrub, through a tomato and pepper

garden and then Fergus led the way through the bushes onto what appeared

to be the beach of a small lagoon.

Alas it was a thin layer of scum floating on the surface of ooze and he

disappeared up to his waist setting up a ripple of slush and mud on the

apparently solid surface. As he slowly began sinking he managed to stop

me laughing, as it really did look funny, and I gave him a hand out. One

sandal got stuck and was left behind, so Fergus consigned the other to

the depths.

|

Now he really needed a swim as he was covered in rotting slime. The

sun was even hotter, and the sand burning. There was nothing for it than

to dash from patch of shade to patch of shade.

The beach was glorious, yellow sand and huge breakers into which Fergus

threw himself and only emerged when he'd managed to get the stench from

out of his nostrils, and his body and clothes were clean.

|

|

|

We set off towards the Togolese border, but on the way we were waved

down by a group of travelers in a Land Rover we'd met in the desert.

They were camped on the beach in front of a small fishing village and

without much trouble persuaded us to stay a few days. I suppose paradise

is dozing on a tropical beach listening to the sound of breakers and

the wind in the palms.

|

|

We helped the villagers pull in the nets with the day's catch. Everybody

who helped was given a share of the haul. Everybody who helped was

given a share of the haul, except us who were spoilt by a present of

prepared fish stew. We lit a fire at night and sat eating fish stew and

drinking coconut milk, totally baked from a day in the sun and clean

from salt water and sand.

|

We quickly crossed the border into Togo and headed towards the

mountains and the spot where we had stayed previously. Although the

farmer was away the three young boys returned after someone had gone to

the next village to tell of our arrival. It was really like seeing old

friends. Before school the boys came to us for breakfast and had their

first cup of cocoa, although we were camped in their father's cocoa

plantation! We promised to write and headed off for an area which we

knew to be swarming with butterflies.

We stopped and left the track to go into the forest. Literally

hundreds of butterflies flitted around us with Fergus attempting to

photograph them. We spent most of the morning chasing and photographing,

but there was one beautiful bright blue butterfly which we could not

take. Various people had passed and stayed a while watching our efforts.

A group of young boys watched for about an hour and then decided to lend

a helping hand. As one of the blue butterflies flitted past he tore off

his shirt and batted it to the ground. We couldn't spoil his obvious

pleasure and pride in his feat by explaining that we really preferred

the butterflies to live, so Fergus placed the two halves of the corpse

together and photographed!

The next stage of our travels would lead us northwards into dry

savannah. We spent our time resting in the cool mountains for a few more

days. We had found a place high up overlooking a huge valley, with the

added attraction of monkeys, who came to drink at the small waterfall

each morning and night. But the longer we delayed the hotter it was

becoming so we packed to move northwards towards the desert once more.

|

|

|

|