|

Motorcyclist Illustrated May, 1976 |

|

part 8by Fergus & Sharyn ReillyBack to the Sahara

|

|

|

As we rode further north in

Togo the bitumen suddenly improved to an extent we were sailing along a

broad expanse, reminiscent of a British motorway, with not another

vehicle in sight -the best road we'd seen in Africa. which abruptly

ended in a small village, returning to the typical rutted dirt road

interspersed with small patches of bitumen. It transpired that this

village was the president's old home and the superhighway was built with

overseas aid money! |

|

|

The road had become deeply

corrugated, but that didn't deter a Honda 90 towing a scooter by means

of an electric flex 300 kilometres northwards over some of the poorest

road we had ridden! We were beginning to worry we might be reduced to

similar measures as my bike developed knocking noises in the engine

and loss of power. Despite Fergus checking all possible sources he

couldn't find the trouble, except to suspect the “fail-proof” timing

regulator. |

We camped the night beside a

river which had been dammed to build a bridge. It was a sanctuary for

birds which skimmed the pools for fish. My romantic day-dreams were

shattered when Fergus stated matter-of-factly that this would be an

ideal place for crocodiles. Suddenly the pools of water linked by

sandbars looked very threatening. I spent the night listening for any

noise of slithering bodies. Fergus's apparent unconcern finally

penetrated so I gave up my vigil and went to sleep. I was never so

glad to wake and see a cloudless day and the peaceful pools of water

below!

|

Although speaking only one or two words of French he happily settled down next to Fergus and watched him working on the motor. Not only was he a monkey catcher, no mean feat as they are very fast, but he grasped mechanics so quickly that he handed Fergus pieces as he reassembled the bike. The young boy's delight on receiving an orange relieved some of the blow of not finding the trouble with the bike. So, we limped into Ouagadougou. After several hours searching for a place to stay, we stopped to ask at a mission for advice. Our luck was changing again, the missionary and his wife offered their guest room which was not being used. Fergus spent the week trying to adjust the timing, after making a tool to release the flywheel. There was a slight improvement so we decided to send back to Britain for the “infallible” timing regulator and to head for Niamey, the capital of Niger. We had read there were potential buyers for our bikes there. It seemed we could sell them at a price to buy our tickets to Australia. Although the week's work on the bike was not particularly successful we thoroughly enjoyed Ouagadougou. Upper Volta is reputedly the poorest country in the world, but the people's unbounded optimism makes them the most generous we had ever met. We spent hours sitting in the market talking to the stall holders, never hassled to buy and instead given tea and nuts for our company. |

The drought of two years

earlier had forced many of the nomadic races into the cities and

Ouagadougou had quite a large number of Tuaregs, the Saharan nomads.

The missionary couple we stayed with introduced us to a young Tuareg

religious man. He instantly became a friend and took us to meet his

friends who made knives and jewellery.

|

His caste prepared pieces of the Koran which were inserted into leather amulets to ward off evil and sickness. having seen the results of juju in other races we couldn't disbelieve his claim that it was possible to create magic to make a person invisible or impenetrable to bullets. The Tuaregs believe totally in the desert. Those forced into the town talked often of returning to the desert when they had enough money to buy the animals, depleted by 80 per cent in the drought. Mustapha explained that there the air is pure and not that breathed in and out by many people. The men are chivalrous like the knights of the Middle Ages, they always are veiled in the presence of women and even sip their tea from underneath the veil. Tuareg women are free to a greater degree than their European counterparts; they retain all the wealth on divorce and either party can dissolve the marriage. But perhaps the most notable characteristics of Tuareg women is their irrepressible joy. They always were laughing, leaving all responsibility to the men, spending hours plaiting each other's hair into intricate patterns or playing with the children. |

Our time and money were

running short so we exchanged gifts and said goodbye to the Tuaregs.

We were carrying letters to their families in Niamey which - they

assured us - they could not do as it would be a prison sentence if they

were caught. |

|

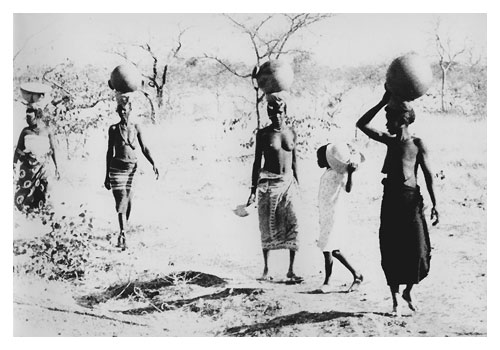

The people sympathised with our problem

and brought us a stool to sit beside the road under a tree. It was

market day and soon we were watching the to-ing and fro-ing of various

sellers. The nomadic cattle herders brought their beautiful tall

wives to the village to sell their spices and to buy cloth or silver.

The men sat with us whilst the women did the selling. The nomads again

impressed us by their self-sufficiency; they asked no questions as to

why we were there but made themselves comfortable and sat peacefully

making idle conversation.

The day passed and not one vehicle had room for the bike. We had

just fallen asleep when a truck screeched to a halt. Someone in the

village must have stopped it. Fergus persuaded the driver to take the

bike and me to the border of Niger, for a sum. The bike was lifted up

and into the truck and I was given a place in the cabin. A few hours

later at dawn we stopped in a tiny village. The men in the back of the

truck jumped down with bundles which they opened up to display cloth

and clothes. From the surrounding bush people appeared and a makeshift

market ensued. The sellers were real actors and if we hadn't been in

the middle of the African bush they could have been English Cockney

tradesmen, bantering with each other and their buyers, and selling at a

furious pace.

At each village the same procedure took place. The truck obviously

served remote villages who were only too glad to turn out at dawn to

buy wares from the “city”.

At each village the same procedure took place. The truck obviously

served remote villages who were only too glad to turn out at dawn to

buy wares from the “city”.

Fergus soon caught us up and followed the truck to the border. The

soldiers on duty there suggested we stop outside their office as all

traffic had to be checked and they would help us find a lift to

Niamey.

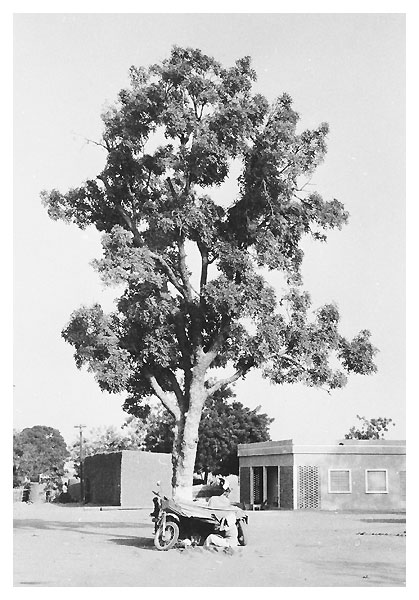

Determined not to miss any possible chance of a lift (we had little

money, water or food on board) we camped in the shelter of a large tree

in front of the customs post where every truck stopped. These behemoths

would roar into the area at all hours of the day and night bringing a

dense cloud of dust which inevitably settled over our makeshift shelter

between the two bikes and soon coated everything we had. We slowly

grew more desperate as our supplies dwindled and not one vehicle had

room for the bike.

Three days later a man in a Peugeot utility offered to take the

bike and me if I was ready in 5 minutes. So we hastily brushed off the

dust, freed the bike from the structure we had made, wedged it between

two refrigerators and set off. Luxury! I was in an air-conditioned

cabin. Fergus was left to pack everything onto his bike and hopefully

meet again in Niamey, he followed at a furious pace but only caught up

with the Peugeot as it entered the outskirts of Niger's capital city and

followed it to the local Catholic Mission.

The first signs of Niamey were the camels carrying goods into the

city in the cool of the night. We met at the catholic mission and

unloaded the bike. We spent the night outside the Archbishop of Niger's

window, guarded by the Tuareg night watchmen and woke to the sound of a

bustling African city.

The next six weeks were six of frustration; the parts took two months

to arrive, and we tried to sell the bikes. Many people showed

interest, but all knew that we were a captive market. So, a long

waiting game was played as the price dropped while our frustration

increased. When we had only $20 left to our name a young American who

befriended us convinced himself to buy the bike. He wanted it, but

couldn't really afford it. But his beautiful Tuareg wife agreed and he

was convinced! He arranged the sale of my bike which had finally been

restored to its former glory by the new part, to a French boy, who

would send us the remaining half of the money in Australia.

The next six weeks were six of frustration; the parts took two months

to arrive, and we tried to sell the bikes. Many people showed

interest, but all knew that we were a captive market. So, a long

waiting game was played as the price dropped while our frustration

increased. When we had only $20 left to our name a young American who

befriended us convinced himself to buy the bike. He wanted it, but

couldn't really afford it. But his beautiful Tuareg wife agreed and he

was convinced! He arranged the sale of my bike which had finally been

restored to its former glory by the new part, to a French boy, who

would send us the remaining half of the money in Australia.

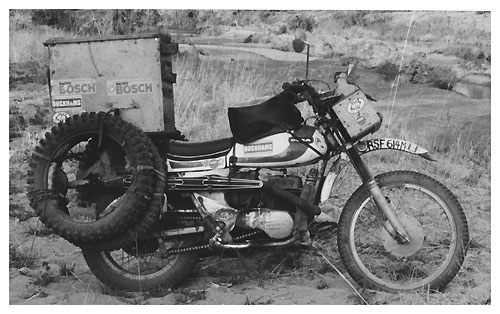

While we were clearly taken advantage of in the very biased buyer's

market, we did end up selling the bikes for more than we had paid for

them, brand-new, in Scotland. They had carried us and our gear for

17,000+ kilometres over some of the world's worst roads and were still

in excellent working order - a tribute to the Spanish engineering.

We were finally set. We had enough money to buy a ticket to

Australia. We nostalgically said goodbye to our bikes which had carried

us for nine months. And to last reports they are fine and working well

and living in the Sahara still.